The mule being a different animal, should be recognized as individuals and trained accordingly; those 63 chromosomes produce a unique and hardy animal that has an emotional side to him as well as a calculating mind that enables him to think things through when approached with a new task from his handler. If you take into consideration the physiological components in a mule, and understand their meaning and what they provide, then working with your mule will now be rewarding and far more productive. The physiological components of the mule are listed below.

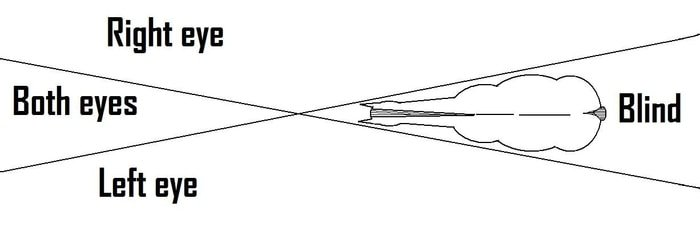

Vision – The mule’s eyes are among the largest of any land mammal and are positioned on the sides of the head. The range of vision is 350°, with approximately 65° of this being binocular vision and the remaining 285°is monocular vision. This enables him to spot predators or potential predators. The mule’s wide range of monocular vision has two “blind spots,” or areas where the animal cannot see: in front of the face, making a cone that comes to a point at about 3–4 ft in front of the mule, and right behind its head, which extends over the back and behind the tail when standing with the head facing straight forward.

The placement of the mule’s eyes decreases the possible range of binocular vision to around 65° on a horizontal plane, occurring in a triangular shape primarily in front of the mule’s face. Therefore, the mule has a smaller field of depth perception than a human. The mule uses its binocular vision by looking straight at an object, raising its head when it looks at a distant predator or focuses on an obstacle to leap over. To use binocular vision on a closer object near the ground, such as a snake or threat to its feet, the mule drops its nose and looks downward with its neck somewhat arched.

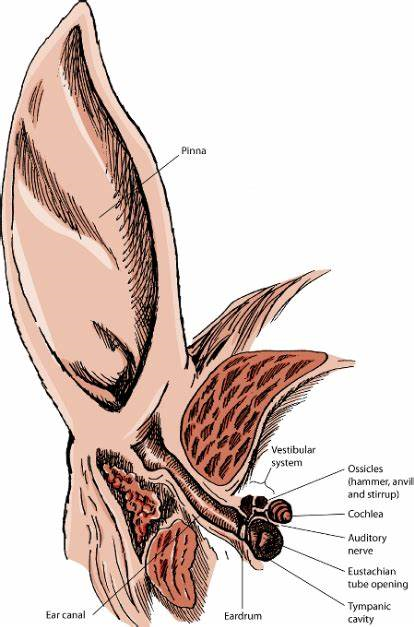

Hearing – Mules hear sounds over a wider range of frequencies than we do, although the decibel levels they respond to are about the same. Humans with good hearing perceive sound in the frequency range of 20 Hertz to as high as 20,000 Hertz, while the range of frequencies for mules is reported as 55 to 33,500 Hertz with their best sensitivity between 1,000 and 16,000 Hertz. The mule’s ears are shaped to locate, funnel, and amplify sounds. Mules have the ability to rotate each ear independently as much as 180 degrees to pay attention to a sound without turning the head. The ears are also used to express and communicate.

Smell – The mule has an acute sense of smell that they regularly employ to provide them with information on what is going on around them. Mules use their sense of smell in many different and important ways. Mother Nature equipped the mule with a strong olfactory sense that can tell the animal whether a predator is near. All it takes is a strong upwind breeze to bring a dangerous scent to the attention of a wild herd of donkeys, mules, and horses. After getting a whiff of the predator, the herd literally high-tails it (their tails stick way up in the air as they flee) out of there in a flash. Although domestic equines are kept in an environment where they are protected from predators, the instinctive behavior of being highly aware of their surroundings is self-inflicted. The mule has developed a high sense of self-preservation and will not approach danger.

Skin – The skin of a mule is less sensitive than that of a horse and more resistant to sun and rain. This makes mules a dependable option for owners who work outside in harsh weather and strong sunlight. Mules are slightly less sensitive to the elements because Mother Nature intended them to be hardy. But remember a mule uses their skin, lips, hair, nose, and their muzzle to their physiological advantage. Their sense of touch is their most acute sense. The mule can sense a fly anywhere it lands on them, and twitch that specific muscle to get the fly off.

The skin also provides a protective barrier, regulating temperature, and provides a sense of touch. Mules from draft horse mares and mammoth jackstock breeding will have a different thickness of skin; their skin will be thicker. Mules from Thoroughbred mares tend to have skin sensitivity issues due to their skin being thinner.

How sensitive a mule is, depends on the age, the training, and the breeding. A mule that is overly sensitive to touch will usually stay that way during his lifetime; it is simply physiological and nothing more. Older mules tend to be less sensitive to touch and appear to be more settled. In addition to being responsive to pressure and pain, mules can also sense vibration, heat, and cold. Mules are capable of bracing the muscles in their body to protect themselves from intense pain (from abuse or a heavy handler) such as a whip or spur.

Researchers from Northwest A&F University in Yangling, China, are doing research on the molecular mechanisms at work in mules that provide this superior muscular endurance. Their genetic testing of samples from crosses between donkeys and horses mapped a total of 68 genes in the “muscle contraction” pathway, eight of which were found to be significantly enriched in mules. In the hybrid individuals and their parents, one of these enriched genes, TNNC2, was mainly expressed in the fast-skeletal (facial) muscle. Its expression level was found to be two times higher in the mule than in the horse. So, if you think that mule is making faces at you, he probably is.

Taste – mules prefer sweet and salty tastes, so they will usually meet their requirement of salt if it is provided in a block form. You can “doctor” a mule’s grain with molasses or honey to eat crushed medicine, however, 90% of the time, the mule is onto you. They use their keen sense of smell to aid them in identifying what is in their bucket. Mules being individuals will be up front with you whether they like or dislike what is on the menu. Some mules refuse treats altogether; others may develop a strong desire for apples, corn or carrots.

The mule I am working with now, insisted we have a trusting relationship before she would accept anything from me in the form of treats or grain. I could halter her, and start working with her, but her heart just wasn’t in it. She needed to know that she could trust me; in other words, her give-a-damn was busted. That’s just who she is. Due to her history, I can understand that; and I don’t blame her for this quirk. Today, we make great riding partners, and…she loves margaritas. [Note: no, do not allow your equine friend to drink alcohol.]